Investigation

This is how the Emirates give Haftar the patrol boats used to push back migrants

The seizure in Spain of ten vessels bound for Benghazi reveals a network of trafficking between Libya, Jordan, the Emirates, and Hong Kong. The role of Operation Irini, Madrid’s silence, and Dubai’s double favor: one for its Libyan ally, the other for Europe, eager to limit departures

“I have a position for you.” The voice recorded on August 2, 2023, by an NGO Sea Watch aircraft belongs to a pilot from the Maltese Armed Forces engaged in a Frontex operation — the EU agency responsible for external border security. The plane is flying over a fishing boat carrying 250 migrants in the central Mediterranean. The radio message is directed at a patrol boat belonging to the coast guard of eastern Libya, controlled by General Khalifa Haftar.

“I have a position for you, if you want it. Were you looking for something? I have a position for you,” says the pilot, adding the boat’s coordinates.

Shortly after, the Tareq Bin Zeyad (TBZ), a large patrol vessel, reaches the spot indicated by the aircraft. Armed militiamen board the fishing boat, tie it with a rope, and tow it back to Benghazi.

The international journalistic investigation that reconstructed this case two years ago — a textbook example of migrant pushbacks coordinated between Europe and a government unrecognized by both the EU and the UN — also revealed the fate of those on board once they were returned to Libya.

“We were beaten and tortured for 22 days. The women were raped,” a Syrian asylum seeker would later recount.

Fast-forward to June 5 of this year

The Madleen sailing boat, part of Greta Thunberg’s Freedom Flotilla and carrying MEP Rima Hassan, is sailing south of Crete towards Gaza to deliver humanitarian aid to Palestinians when it receives an emergency call. Frontex asks for urgent assistance to rescue about forty migrants who had left Libya on a rubber dinghy now adrift.

As soon as the Madleen reaches the boat in distress, it is approached by a large patrol vessel, the TBZ3, which warns the activists to stay away. Fearing deportation to Libyan detention centers, four migrants jump into the sea and swim to the sailboat; the others are picked up by the patrol boat and taken back to Benghazi. The survivors say they were fleeing the war in Sudan.

How did Haftar acquire the TBZ and TBZ3?

Understanding who allowed Haftar to equip himself with such military assets helps explain how the systematic violation of the arms embargo in Libya ultimately benefits European states, which prefer the Cyrenaican general to have the means to stop migrant flows.

Il Foglio has reconstructed the chain of events — beginning last August — that led to the seizure in Spain of a shipment of patrol boats used for illegal migrant pushbacks, originating from the United Arab Emirates and bound for Benghazi, in violation of the UN arms embargo. Such seizures are rare:

“Most of the military material sent to Libya from the Gulf or Turkey manages to pass through the Mediterranean undetected,”

confides a diplomatic source to Il Foglio.

Despite the exceptional nature of the seizure, all European actors involved — from Spain to the EU’s Operation Irini, and even the European Commission — chose not to publicize the event.

From Dubai to Benghazi

Jeremy Binnie, analyst at Jane’s (the world’s leading open-source platform on defense and security), told us that in June this year, the cargo ship Bahri Diriyah delivered several vessels to Benghazi, all built by the Grandweld shipyards in Dubai.

Brand new, among them were four patrol boats — all carrying the TBZ designation, after the Tareq Bin Zeyad Brigade commanded by Saddam Haftar. According to the UN, this brigade is responsible for war crimes and human rights abuses against migrants.

It is this same brigade — also supported by Russian Wagner mercenaries — that Europe relies on to control the migration routes from eastern Libya toward Greece, Malta, and Italy. They are, effectively, doing Europe’s “dirty work”: the pushbacks. A practice illegal under international law but now a pillar of EU migration strategy.

The Spanish Seizure

The June shipment was just one part of a larger delivery from the Emirates to Haftar. The second batch, due in July, went wrong thanks to Spanish authorities and Operation Irini, which — under a UN mandate — monitors compliance with the arms embargo.

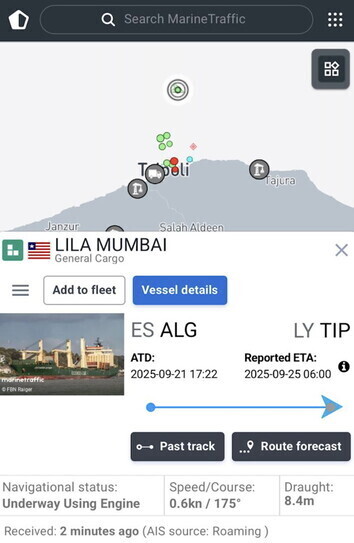

On July 18, the Lila Mumbai, a Liberian-flagged cargo ship, left the Emirati port of al-Fujayrah bound for Benghazi. Forced to sail around Africa due to the Red Sea conflict, the ship carried several large vessels visible on deck, some covered with white tarps.

Upon crossing the Strait of Gibraltar on August 27, Spain’s Guardia Civil stopped the Lila Mumbai at Ceuta for suspected arms embargo violations. Local newspaper El Faro de Ceuta reported that the interception order came from Spain’s Foreign Ministry. The European Commission declined to comment, but Operation Irini confirmed its central role:

“The operation alerted Spanish authorities to the opportunity for inspection, enabling timely action,” an Irini source told Il Foglio.

Since 2020, Irini has directly seized arms-bound shipments to Libya only twice — both in 2022. Usually, EU member states handle such cases based on Irini’s “suggestions.”

The Lila Mumbai seizure was kept quiet: no press releases, no social media posts. The ship was escorted to the port of Algeciras for further inspection. On September 18, broadcaster Europasur filmed the offloading of ten vessels — eight fast boats and two large patrol boats.

One of them bore the identification code IMO TBZ17 — allowing investigators to trace its history.

Tracing the Ships’ Ownership

Both the TBZ17 and its twin, the TBZ18, were built by Grandweld, the same Emirati yard as all TBZ-class ships delivered to Benghazi since 2023. Newly built, the TBZ17 was registered under the flag of St. Kitts and Nevis on May 2 this year.

Curiously, just days before the Lila Mumbai was intercepted, on July 24, the TBZ17 was deregistered.

According to the Lloyd’s List Seasearcher database, from May 21 the ship’s owner was Multham International Ltd, a company registered in Hong Kong. Before that, according to Vessel Finder, it was owned by 2020 Volume Boats Maintenance & Repairing Ltd, based in Dubai — the same company that appears in UN reports as a serial violator of the arms embargo.

The Network Behind the Ships

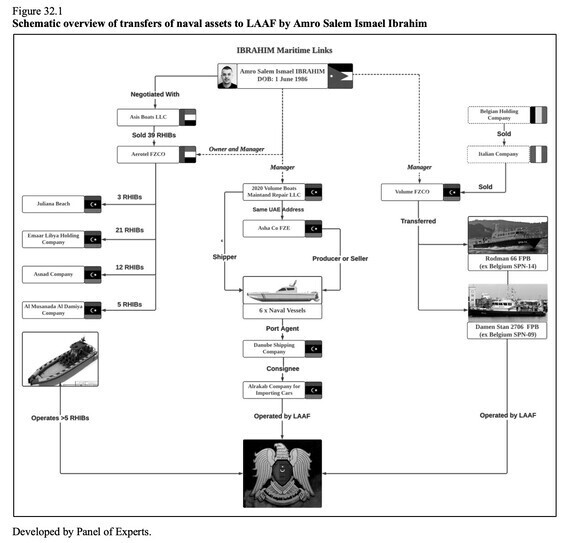

The UN Panel of Experts on Libya (December 2024 report) identifies Volume 2020 Boats Maintenance & Repairing Ltd as owned by Amro Ibrahim, a Jordanian citizen based in the UAE. Between 2023 and 2024, his companies sent multiple naval units to Benghazi, directly to entities controlled by the Haftar family — 41 inflatable boats and 5 patrol vessels.

Two of these had an unusual path: Belgian Coast Guard ships (Rodman 66 and Damen Stan 2706) sold to an unnamed Italian company, which then resold them to another of Ibrahim’s companies, Volume FZCO, that delivered them to Benghazi in March 2023.

Even the first TBZ — the same ship involved in the migrant pushback with European coordination — belonged to 2020 Volume Boats Maintenance & Repairing Ltd. On LinkedIn, a man identifying as Indian lists himself as a “supervisor” for 2020 Volume by Asha Co. in Bayda, near Benghazi.

The Hong Kong Connection

How, then, did ownership transfer from the Emirati company to Hong Kong’s Multham International Ltd?

According to LinkedIn, Volume FZCO explains:

“We were founded in Jordan in 2014, expanded to the UAE in 2017, and to Hong Kong in 2020.”

Hong Kong business records show that Multham International Ltd — the official owner of Haftar’s TBZ ships — belongs to another Jordanian, Omar Mahmoud Hasan Mustafa, who also owns Qingdao Haoding International Trading Co. Ltd in China, specializing in boats and auto parts.

Both men, Ibrahim and Mustafa, declined Il Foglio’s interview requests. A Hong Kong management firm representing Multham confirmed only:

“We will inform Mr. Mustafa of your inquiry; it is up to him whether to respond.”

Experts suggest that this may be a sale-and-leaseback scheme common in maritime trade, allowing real owners to hide behind nominal shell companies in jurisdictions like Hong Kong.

Spain’s “No Comment” and Growing Tensions

Madrid refused to comment officially on the Lila Mumbai case.

“Relations with Haftar are already tense; they don’t want new friction with Cyrenaica,”

a source close to PM Pedro Sánchez told Il Foglio.

The rift touches multiple fronts — arms, oil, even sports. Last week, FC Barcelona was expected in Benghazi for a football tournament at a new stadium built by the Haftar family. The eastern Libyan authorities had already paid the club €5 million in advance, but Barça suddenly pulled out, citing “security concerns.” The affront angered the Haftars, prompting protests and a complaint letter from the Tobruk Parliament to the Spanish embassy. Atlético Madrid has since been invited to play instead.

The arms issue runs deeper: in December 2024, El Independiente revealed an investigation into three Spanish firms accused of supplying Haftar with 44 drones worth nearly €15 million. Spain issued an arrest warrant for Saddam Haftar, the general’s son.

Yet in July last year, Saddam flew to Genoa under a false name, only to be detained days later in Naples — using his real passport this time. Italian police held him briefly, weighing Spain’s request for extradition. In the end, he was released and flown back to Libya, enraging his father. Haftar retaliated by ordering the shutdown of the Sharara oil field — one of the world’s largest — operated by Spain’s Repsol.

Europe’s Dilemma

While Spain wages its own war against Haftar by seizing boats and drones meant for migrant control, Greece, Malta, and Italy bear the consequences — as main landing countries for migrants from eastern Libya. With full European Commission backing, border externalization — even via Haftar — has become a cornerstone of EU migration policy.

For the EU, the UAE is a convenient partner. Abu Dhabi pursues its own agenda in Cyrenaica, using it as a hub to supply arms to Sudan and Chad, where Emirati companies hold vast gold-mining interests. Almost daily, flights from Abu Dhabi bring weapons and vehicles to southern Libyan airports, which Haftar allows through in exchange for “gifts” — like the vessels aboard the Lila Mumbai — strengthening his grip on migration routes.

Unanswered Questions

Two mysteries remain after the Spanish seizure. Once the ten vessels were confiscated and the ship released, the Lila Mumbai sailed to Tripoli — a stop not originally planned — arriving on September 26 and staying a day and a half, long enough to unload “something else.”

A similar pattern occurred last August with the Aya 1, another Emirati cargo ship stopped in Greece while carrying armored pickup trucks bound for Haftar. It was later allowed to continue to Misrata, from where part of the cargo reached Benghazi by land.

Rumors now suggest the EU is trying to redirect seized military equipment to Tripoli — ostensibly to strengthen the only internationally recognized Libyan government. One case in point: the MV Meerdijk, seized in 2022 with armored vehicles, still docked in Marseille.

In theory, such transfers could bypass the embargo under the pretext of supporting legitimate authorities. In practice, as the Aya 1 case shows, those weapons often end up in Haftar’s hands anyway.

Neither Operation Irini nor the European Commission have commented on the matter.